Frequently Asked Questions¶

What are the conventions for excitation operators/integrals/orbital indices…¶

The convention for indices of excitation operators and qubit ordering is as follows:

An excitation operator is represented by a tuple of integers. Each integer corresponds to one spin-orbital.

The first half of the tuple contains the indices for creation operator and the second half is for annilation operator.

Hermitian conjugation is handled internally.

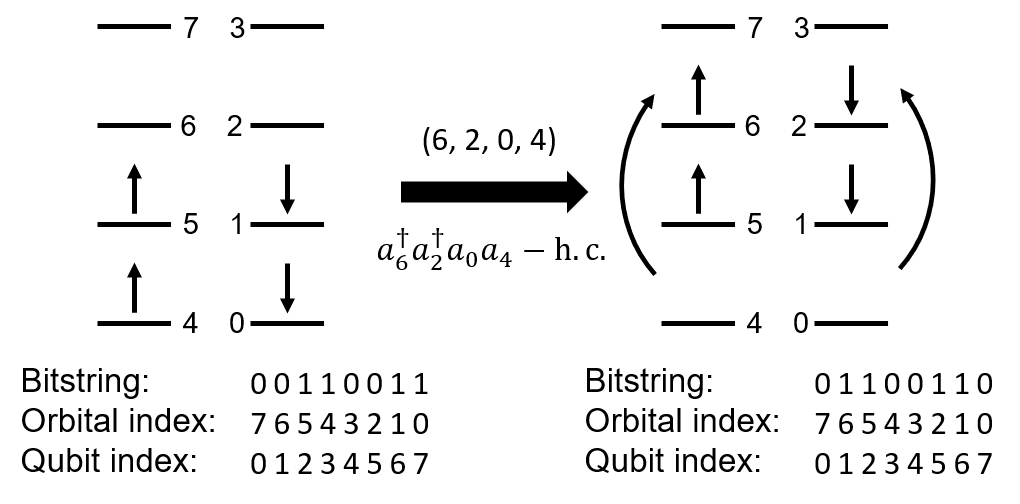

Or, (6, 2, 0, 4) corresponds to \(a^\dagger_6 a^\dagger_2 a_0 a_4 - a^\dagger_4 a^\dagger_0 a_2 a_6\).

Besides, the spin-orbitals are indexed from 0 and ordered according to the following rules

Beta (down) spins first, followed by alpha (up) spins

Low energy orbitals first, followed by high energy orbitals

Qubits are numbered from 0, with multiqubit registers numbered with the zeroth qubit on the left,

e.g. \(|0\rangle_{q_0} |1\rangle_{q_2} |0\rangle_{q_2}\).

In UCC classes, the occupancy of spin-orbital \(i\)

(using the above ordering) corresponds to the state of qubit \(N - 1 - i\) where \(N\) is the total number of qubits.

In other words, the qubit ordering is reversed spin-orbitals ordering.

This convention is best understood from a bitstring picture.

Each molecular orbital configuration can be represented as a bitstring in occupation number space.

For example, the HF state of \(\rm{H}_4\) can be represented as 00110011.

Counting the bitstring from left to right gives the spin-orbital index.

An important reason for keeping the convention is to be consistent with pyscf.fci.cistring.

In short, the convention for excitation operators and spin-orbital indices can be summarized in the following figure:

Following the qubit indexing convention above, the restricted Hartree-Fock state for such a system is represented as 00110011 in bitstring form. The highest orbital with \(\alpha\) spin comes first in the bitstring, and the lowest orbital with \(\beta\) spin comes last. In quantum chemistry language, 00110011 refers to a configuration with orbitals 5, 4, 1, and 0 occupied, while in quantum computating language, 00110011 refers to a direct product state with the 2nd, 3rd, 6th, and 7th qubits in state \(|1\rangle\) and the rest in state \(|0\rangle\). Upon application of the excitation operator (6, 2, 0, 4), the HF state transforms to 01100110.

The integrals such as ucc.int2e are stored in the Chemists’ Notation \((ij|kl)\)

without considering symmetry.

Note that although in excitation operators the orbitals with the same spin are indexed from high-energy to low-energy,

in the integrals the orbitals are indexed from low-energy to high-energy.

In general, TenCirChem tries to match the convention of PySCF. For example, the distance unit is angstrom, and the configuration interaction vector can be fed into PySCF directly.

There’s also a naming convention for excitation operators in the source code.

Excitation operators in the bare tuple form are usually named as ex_op,

and after transformed to OpenFermion operator they are usually named as fop.

Why are the number of excitation operators and the number of parameters different?/What is param_ids?¶

Some excitations share the same parameter due to symmetry.

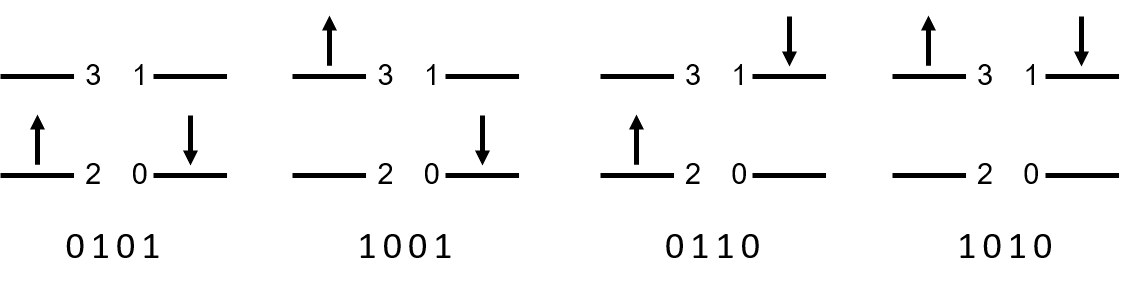

For example, 1001 and 0110 configurations have the same amplitude.

Thus, (0, 1) and (2, 3) excitations can use the same parameter.

This is why the number of excitation operators is usually larger than the number of parameters.

param_ids is a list of integers that maps excitations to parameters, starting from 0.

Its size is the number of excitations, and its largest value plus one is the number of parameters.

This parameter sharing strategy improves VQE convergence and accuracy. To disable it, try the following

ucc.param_ids = None

ucc.init_guess = np.zeros(ucc.n_params) # n_params equals number of excitations

Why is TenCirChem so fast?¶

The speed of TenCirChem depends on the underlying engine.

For the "civector" and "civector-large" engines,

there are three main factors that makes them fast

The quantum state is represented in CI space rather than the full Hilbert space. Take the hydrogen molecule as an example. The four quit system has a dimension of \(2^4=16\). On the other hand, the possible configurations, constrained by the particle number in each spin sector, are

"0101","1001","0110"and"1010",

The excitation operator exponential \(e^{\theta G}\) is expanded in a polynomial form, rather than decomposed into quantum gates. See Engines for more details.

Excitations are implemented as efficient bitstring manipulations.

TenCirChem also has an efficient algorithm to calculate UCC gradient, described in How does TenCirChem evaluate UCC gradient?.

How does TenCirChem evaluate UCC gradient?¶

In general there are two ways in TenCirChem to evaluate energy gradient with respect to parameters in UCC. The first is by JAX auto-differentiation. The related concepts can be found in JAX documentation.

The second method is hard-coded gradient, which is generally more efficient.

Suppose the ansatz has the form

and \(|\psi \rangle\) is real. Define

The energy expectation can be written as

then the energy gradient is

In practical implementation, \(\langle \phi^{(1)}_{M+1} |=\langle \psi | \hat H\) and \(| \phi^{(2)}_{M} \rangle = |\psi \rangle\) are firstly calculated after \(| \psi \rangle\) is obtained. Then, \(\langle \phi^{(1)}_j |\) and \(| \phi^{(2)}_{j-1} \rangle\) are obtained by the recursion relation

For each pair of \(\langle \phi^{(1)}_{j} |\) and \(| \phi^{(2)}_{j-1} \rangle\), \(\frac{\partial \langle E \rangle}{\partial \theta_j}\) is calculated. Thus, this algorithm computes all gradients in one sweeping pass, requiring a constant amount of memory.

How to use GPU in TenCirChem?¶

Choosing device is done by choosing backend for TenCirChem. TenCirChem by default uses NumPy backend, and supports JAX and CuPy backend. Both JAX and CuPy supports GPU. Install JAX and CuPy with appropriate GPU driver and set the backend in the following way

from tencirchem import set_backend

set_backend("cupy") # or "jax"

More fine-grained control over the devices is achieved through the JAX or CuPy package

import cupy as cp

# use the second GPU

cp.cuda.Device(1).use()

Why is JAX backend so slow on first run?¶

JAX features JIT compilation, and the compile time can be quite long for typical TenCirChem use cases. In TenCirChem, it is common that the JIT compilation time is much longer than the actual optimization time. TenCirChem has already optimized the compilation speed, yet there are simply too many instructions in typical UCC circuit. The JAX document offers more information on slow compilation.

If you’re using CPU based JAX, switching to the GPU version can significantly speed up compilation. Otherwise, to the author’s knowledge currently there’s no way to solve the slow compilation problem.